I’ve decided to honor the decision by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Royal Concertgebouw to have an online version of the Mahler Festival by offering my favorite performances of the symphony that the festival is broadcasting each day.

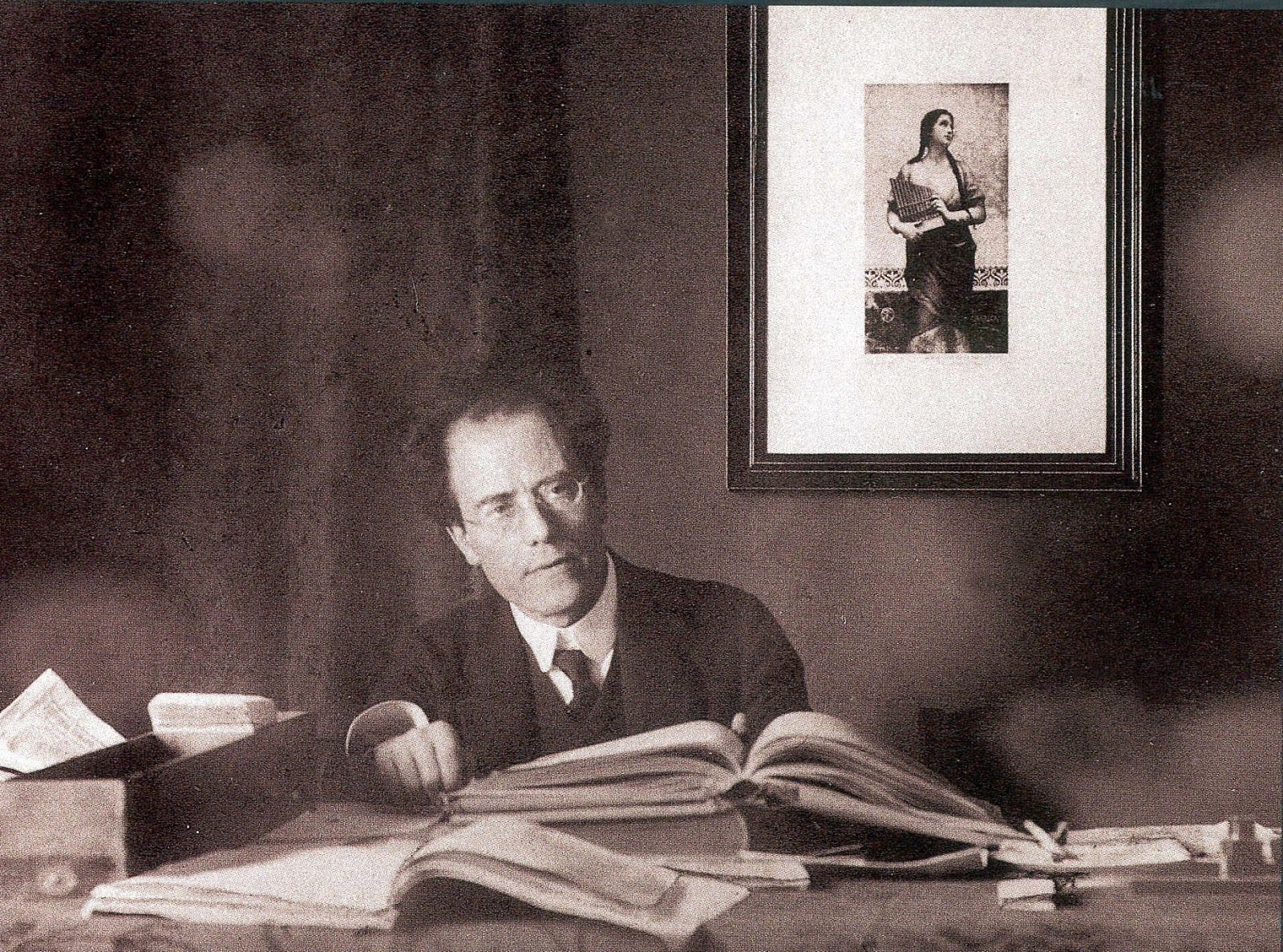

Gustav Mahler ascended to the throne of the conducting profession in 1897, when he became the General Music Director of the Vienna Court Opera, now the Vienna State Opera. It was music’s most prestigious position and with it came an enormous responsibility. Mahler was everywhere and ran the opera house with an iron fist. Modern stage direction, lighting, set design were all in their infancy in opera and Mahler held a tight grip on all of it!

His fourth symphony, composed during the summers of 1899 and 1900, was the first he composed after being hired in this position, and it’s interesting that the subject matter and general mood of the symphony is in direct opposition to the hectic conducting life he had at the time. Also, rather than working in a little ‘hut’ behind a small hotel at Steinbach am Attersee, Mahler could now afford to rent a villa. He chose the Villa Kerry, a 30-minute walk above the the lake, Altaussee. Unfortunately, the weather for most of that summer was cold and wet and it turned that this villa was in earshot of the local bandstand. He was only able to compose part of the symphony at the very end of his holiday symphony.

The following summer (1900) was spent in his newly built composing hut on the property where his villa was being built, in Maiernigg, a tiny village on the shores of the Wörthersee.

Like Beethoven’s Symphony №4 in relation to his Symphony №3 ‘Eroica,’ Mahler’s Symphony №4 is restrained and classical in size and structure compared to his gargantuan Symphony №3. It has the standard four movements, but it retains one special characteristic that was unique to the previous three symphonies — there is a vocal soloist. For the last movement, Mahler uses Das himmlische Leben (The Heavenly Life), a song that he wrote in 1892 based on a poem from the collection, Das Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn). For a wonderful English translation, please of the poem, please go here.

The first three movements, while not having a text, certainly help form a narrative of a child’s view of the world. Indeed, all four movements contain themes that resemble children’s songs more than anything else. Here are my favorite performances.

Das himmlische Leben (aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn)

Wir genießen die himmlischen Freuden, D’rum tun wir das Irdische meiden. Kein weltlich’ Getümmel Hört man nicht im Himmel! Lebt alles in sanftester Ruh’. Wir führen ein englisches Leben, Sind dennoch ganz lustig daneben; Wir tanzen und springen, Wir hüpfen und singen, Sankt Peter im Himmel sieht zu.

Johannes das Lämmlein auslasset, Der Metzger Herodes d’rauf passet. Wir führen ein geduldig’s, Unschuldig’s, geduldig’s, Ein liebliches Lämmlein zu Tod. Sankt Lucas den Ochsen tät schlachten Ohn’ einig’s Bedenken und Achten. Der Wein kost’ kein Heller Im himmlischen Keller; Die Englein, die backen das Brot.

Gut’ Kräuter von allerhand Arten, Die wachsen im himmlischen Garten, Gut’ Spargel, Fisolen Und was wir nur wollen. Ganze Schüsseln voll sind uns bereit! Gut’ Äpfel, gut’ Birn’ und gut’ Trauben; Die Gärtner, die alles erlauben. Willst Rehbock, willst Hasen, Auf offener Straßen Sie laufen herbei! Sollt’ ein Fasttag etwa kommen, Alle Fische gleich mit Freuden angeschwommen! Dort läuft schon Sankt Peter Mit Netz und mit Köder Zum himmlischen Weiher hinein.[note 1] Sankt Martha die Köchin muß sein.

Kein’ Musik ist ja nicht auf Erden, Die unsrer verglichen kann werden. Elftausend Jungfrauen Zu tanzen sich trauen. Sankt Ursula selbst dazu lacht. Kein’ Musik ist ja nicht auf Erden, Die unsrer verglichen kann werden. Cäcilia mit ihren Verwandten Sind treffliche Hofmusikanten! Die englischen Stimmen Ermuntern die Sinnen, Daß alles für Freuden erwacht.