By Donato Cabrera│medium.com/@donatocabrera

September 13, 2020

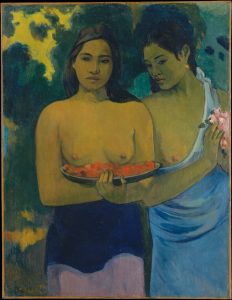

Composed in 1899, Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) represents the hyper expressivity that was flourishing in the arts. While in polite society displaying one’s emotions was frowned upon, the most subtle and private feelings were being explored by artists in all media, from Paul Gaugin’s Two Tahitian Women,

and J.W. Godward’s The Mirror

to Constantin Meunier’s The Horse at the Pond

The expression contained in these works of art, both of the subjects and of the artists, are in anxious suspension, wanting to burst forth if only they could be animated into flesh and blood.

The music that was being composed at this time also had emotion bubbling out of the kettle and Verklärte Nacht is a prime example. Inspired by the hyper-expressive eponymous poem by Richard Dehmel, Schoenberg composed the music to strictly follow the dramatic content of every stanza.

Zwei Menschen gehn durch kahlen, kalten Hain;

der Mond läuft mit, sie schaun hinein.

Der Mond läuft über hohe Eichen;

kein Wölkchen trübt das Himmelslicht,

in das die schwarzen Zacken reichen.

Die Stimme eines Weibes spricht:„Ich trag ein Kind, und nit von Dir,

ich geh in Sünde neben Dir.

Ich hab mich schwer an mir vergangen.

Ich glaubte nicht mehr an ein Glück

und hatte doch ein schwer Verlangen

nach Lebensinhalt, nach Mutterglückund Pflicht; da hab ich mich erfrecht,

da ließ ich schaudernd mein Geschlecht

von einem fremden Mann umfangen,

und hab mich noch dafür gesegnet.

Nun hat das Leben sich gerächt:

nun bin ich Dir, o Dir, begegnet.“”Sie geht mit ungelenkem Schritt.

Sie schaut empor; der Mond läuft mit.

Ihr dunkler Blick ertrinkt in Licht.

Die Stimme eines Mannes spricht:„Das Kind, das Du empfangen hast,

sei Deiner Seele keine Last,

o sieh, wie klar das Weltall schimmert!

Es ist ein Glanz um alles her;

Du treibst mit mir auf kaltem Meer,

doch eine eigne Wärme flimmert

von Dir in mich, von mir in Dich.Die wird das fremde Kind verklären,

Du wirst es mir, von mir gebären;

Du hast den Glanz in mich gebracht,

Du hast mich selbst zum Kind gemacht.“

Er faßt sie um die starken Hüften.

Ihr Atem küßt sich in den Lüften.

Zwei Menschen gehn durch hohe, helle Nacht.Two people are walking through a bare, cold wood;

the moon keeps pace with them and draws their gaze.

The moon moves along above tall oak trees,

there is no wisp of cloud to obscure the radiance

to which the black, jagged tips reach up.

A woman’s voice speaks:“I am carrying a child, and not by you.

I am walking here with you in a state of sin.

I have offended grievously against myself.

I despaired of happiness,

and yet I still felt a grievous longing

for life’s fullness, for a mother’s joysand duties; and so I sinned,

and so I yielded, shuddering, my sex

to the embrace of a stranger,

and even thought myself blessed.

Now life has taken its revenge,

and I have met you, met you.She walks on, stumbling.

She looks up; the moon keeps pace.

Her dark gaze drowns in light.

A man’s voice speaks:“Do not let the child you have conceived

be a burden on your soul.

Look, how brightly the universe shines!

Splendour falls on everything around,

you are voyaging with me on a cold sea,

but there is the glow of an inner warmth

from you in me, from me in you.That warmth will transfigure the stranger’s child,

and you bear it me, begot by me.

You have transfused me with splendour,

you have made a child of me.”

He puts an arm about her strong hips.

Their breath embraces in the air.

Two people walk on through the high, bright night.

(English translation by Mary Whittall)

A poem of such frankness and acceptance of a situation, that even today would still be considered complicated, is yet another example of the multitude of emotional ambiguities that were for the first time being explored.

Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, like the poem, is divided into five sections and, like the music of his teacher, Alexander von Zemlinsky, attempts to combine the formal logic of the music of Johannes Brahms with the hyper-chromatic and dramatic nature of the music of Richard Wagner. He originally scored it for a string sextet — two violins, two violas, and two cellos. In 1917, he created a version for string orchestra and later revised this version in 1943.

Here are some of my favorite performances of the string sextet version.

And the string orchestra version.