By Donato Cabrera│medium.com/@donatocabrera

October 20, 2020

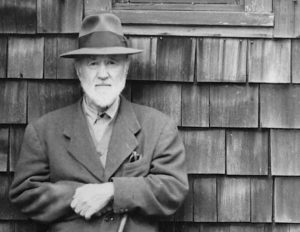

Charles Ives was born on this day in 1874. Born to abolitionists and civic leaders, Mary Elizabeth and George Ives, in Danbury, Connecticut, Charles had what seemed a very traditional New England upbringing. He attended the Hopkins School and Yale University, was a very popular student who excelled in all sports — he played baseball and football for Yale — and went into the insurance business. He would eventually start his own insurance company and is widely considered the father of what is now known as estate planning. It is ironic that during his lifetime he was well-known in the insurance world and not known as a composer and, now, most know him as a composer without knowing his enormous contributions to the insurance business!

What was untraditional in Ives’ upbringing was his musical education. His father, George Ives, was a conductor of bands, choirs and orchestras, and during the Civil War was a U.S. Army bandleader. Ives taught his two sons, Charles and James, music and encouraged them to be inventive and experimental in composition. Charles’ penchant for writing bitonal and polyrhythmic music comes from these early lessons and would prove to be a seminal influence in practically all of Charles’ compositions.

Known as the Concord Sonata, Ives began writing his Piano Sonata №2, Concord, Mass., 1840–60 in 1904. Originally published in 1920, Ives extensively revised it, like his did all of his pieces, and the version that is now performed was published in 1947. It is a work dedicated and inspired by the transcendentalists associated with Concord, Massachusetts. In his 124-page Essays Before a Sonata, Ives writes that the work was his,

impression of the spirit of transcendentalism that is associated in the minds of many with Concord, Massachusetts of over a half century ago. This is undertaken in impressionistic pictures of Emerson and Thoreau, a sketch of the Alcotts, and a scherzo supposed to reflect a lighter quality which is often found in the fantastic side of Hawthorne.

The four movements are titled:

- “Emerson” (after Ralph Waldo Emerson)

- “Hawthorne” (after Nathaniel Hawthorne)

- “The Alcotts” (after Bronson Alcott and Louisa May Alcott)

- “Thoreau” (after Henry David Thoreau)

It is an incredibly experimental piece, especially considering when it was written. Most of the music doesn’t have any bar-lines and there are moments where Ives requires the pianist to depress the keys with a piece of wood or the palm of the hand to create “cluster chords.” Ives’ intention was to somehow create a sense of freedom and improvisation that was not only in line with the philosophical underpinnings of transcendentalism, but also to create a sense of prose and recitation that would naturally differ from performer to performer.

There are many pianists that perform it now, but for most of its published existence, John Kirkpatrick was the pianist most associated with this nearly hour-long behemoth. He was the first to record it in 1945 (released in 1948) and this recording remains essential.

Other great recordings include those by Marc-André Hamelin.

and Jeremy Denk.

One of the great feats of orchestration, in my opinion, is Henry Brant’s brilliant version of the sonata for full orchestra called, A Concord Symphony. Of the many recordings I was involved with during my tenure with the San Francisco Symphony, our recording of this masterpiece is a highlight.

And for all of the thorniness that most associate with this incredibly dense work, I leave you with a 1943 recording of Ives playing the intensely touching and movement third movement of the Concord Sonata, The Alcotts.