By Donato Cabrera│medium.com/@donatocabrera

October 14, 2020

We celebrated the birthday a few days ago of one of my favorite composers, Ralph Vaughan Williams. And while I love all of his symphonies, I most often come back to his Symphony №5.

Vaughan Williams spent the majority of WWII working on this symphony, beginning in 1938 and finishing it in 1943. It is a ‘war symphony’ unlike any other. Compared to the two other fifth symphonies written during WWII — Prokofiev’s and Shostakovich’s — it’s character and content is dramatically different. It is music of serenity, solemnity, and fortitude. If the British motto from the same era were made manifest in music, Vaughan Williams’ Symphony №5 would be what was heard.

Vaughan Williams dedicated the symphony to Jean Sibelius, whom he greatly admired. Sibelius showed nothing but gratitude and wrote in a letter to Adrian Boult,

I heard Dr. Ralph Vaughan Williams’ new Symphony from Stockholm under the excellent leadership of Malcolm Sargent … This Symphony is a marvellous work … the dedication made me feel proud and grateful … I wonder if Dr. Williams has any idea of the pleasure he has given me?

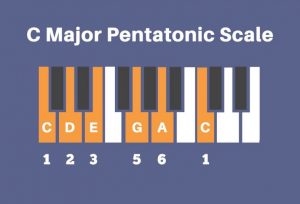

The symphony has four movements and from the very beginning, one can hear not only the expansiveness and harmonic fingerprint of Sibelius, but also Vaughan Williams’ love of English folk music, which is often based on the pentatonic scale. As the name implies, it is a scale based on just five notes.

The pentatonic scale can be found throughout the world, regardless of culture, and is found throughout this symphony. Here’s an amazing example of how the pentatonic scale is in our DNA.

The first movement begins with what sounds like a distant call from the horns, followed by the violins which play a pentatonic scale. What these two things achieve is a sense of mystery, not only in its emotional content, but the way in which it’s composed. Perhaps this is why Vaughan Williams titled this movement, Preludio.

The second movement is a scherzo which focuses more on rhythm than melody. Like most scherzos, the music is fast and playful but there is an otherworldliness to it that keeps it from sounding frantic or too rambunctious. There is, indeed, a chorale-like second theme that pops up throughout the movement that connects it rather well to the first movement and what is to follow.

And what follows is perhaps one of the most serene pieces of music ever written, the third movement which Vaughan Williams titled, Romanza. In the manuscript, he wrote these words from Bunyan,

Upon that place there stood a cross

And a little below a sepulchre … Then he said

“He hath given me rest by his sorrow and

Life by his death”

It is a meditation and one can hardly imagine the impact music of this depth of feeling had on the audience at the premiere.

The fourth movement is a celebratory, yet gentle Passacaglia. A passacaglia is a theme that is constantly repeated throughout the movement and was a very popular dance in the renaissance. However, Vaughan Williams doesn’t stick to this formula and brings back the themes from the first movement in a very contemplative and valedictory way, quietly ending the symphony in a peace and calmness.

John Barbirolli and his Hallé Orchestra were the first to record it in early 1944. It has it merits and the spirit of the piece certainly shines through, even today.

However, Barbirolli’s second recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1962 is considered one of the greatest ever made and it’s atmosphere is so special.

Here is another favorite recording with Andre Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra.

Finally, here is a very performance from the 2012 Proms with Andrew Manze and the BBC Scottish Orchestra.