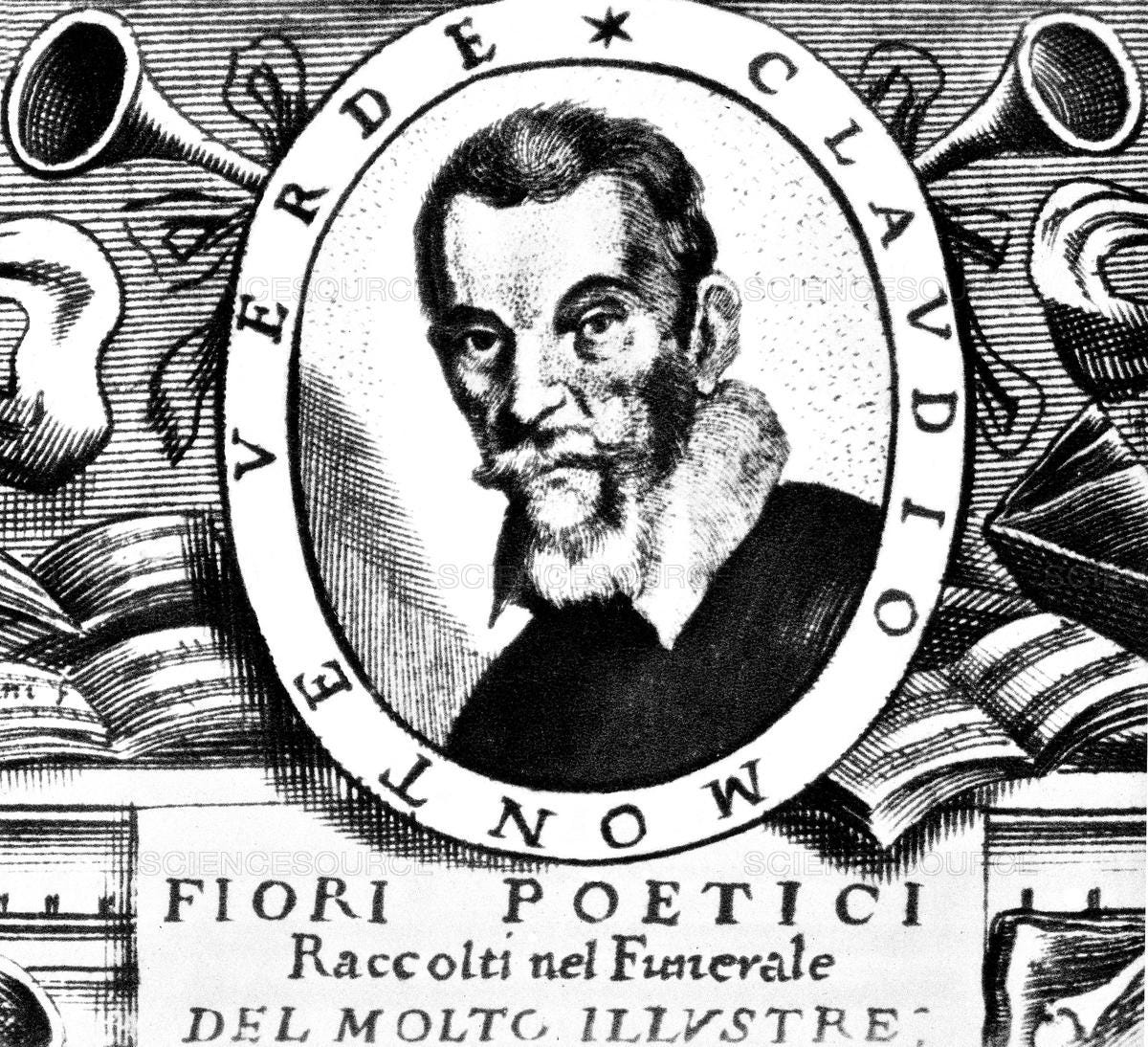

As I mentioned in my last blog, the music of Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) represents for me the transition to a style of composition that, more or less, is still used today. Much of his music is unfortunately lost but what remains shows a path forward from the Renaissance to the Baroque, from science to sensuality.

Born in Cremona, Monteverdi’s early years aren’t well documented. His father was an apothecary and his mother died when he was seven and he studied composition and counterpoint with the maestro di capella of the Cremona Cathedral, Marc’Antonio Ingegneri. By the age of 24, Monteverdi was hired by the rather infamous Duke of Mantua, Vincenzo Gonzaga, and worked for Gonzaga for over twenty years.

During his many years in Mantua, Monteverdi wrote the remaining books of his Madrigali. In a previous post I’ve shared Book IV. Here is Book III from 1592, the book of madrigals written under the employ of Duke Gonzaga.

Monteverdi’s first compositional success, L’Orfeo, stunned the Mantuan court in its 1607 premiere. His brilliant way of using what were then secular instruments, the violin and the cornetto, as well as writing virtuoso arias and ensembles for the singers that were incredibly dynamic and dramatic in nature, were revolutionary. The story of Orpheus, a musician who uses his instrument and voice to win back his love, Eurydice, from the grips of hell, must’ve been very close to Monteverdi’s heart and it shows.

Here are three beautifully staged performances:

And the famous 1978 Ponelle film:

Monteverdi’s success with L’Orfeo gave him the confidence to write his Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers of the Virgin Mary) in 1610 in order to find employment at the Papal court in Rome. He was unable to secure an audience with the Pope and, moreover, his clandestine journey to Rome was discovered by a Mantuan official. It wasn’t until the death of Vincenzo Gonzaga in 1612, afterwhich Monteverdi was unceremoniously fired by Gonzaga’s son, the new Duke with new austerity measures. In 1613, Giulio Cesare Martinengo, the maestro di cappella of the San Marco Basilica in Venice, died. Monteverdi, most likely using the Vespers as his calling card, got the job and remained there for the rest of his career.

This is an absolutely excellent hour-long documentary made for BBC Two about Monteverdi and the Vespers.

For some reason probably having to do with random music buying sprees, one of the first laserdiscs, that’s right laserdiscs, I ever owned was when John Eliot Gardiner’s now famous second recording of the Vespers, filmed in the San Marco Basilica, was released in 1990.

The video release came with a beautifully shot mini-documentary and I was able to find both on YouTube.

Another great performance from Gardiner and his Monteverdi Choir beautifully filmed in palace of Versailles in 2014.

And, as usual, a committed and excellent Dutch performance by the Green Mountain Project from 2019.

Monteverdi’s final opera, L’incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea) from 1643 is also essential listening and is imbued with music by the hand of a true master. The now 76 year-old composer had achieved famed throughout Europe and, like Verdi’s last opera, Falstaff, every note is placed with love and care.

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle also staged and filmed Poppea.

An excellent modern staging by Claudio Cavino with Davide Pozzi conducting the excellent period performance group, La Venexiana

Finally, a powerfully semi-staged performance in Venice’s La Fenice Opera House with Sir John Eliot Gardiner conducting his Monteverdi Choir.