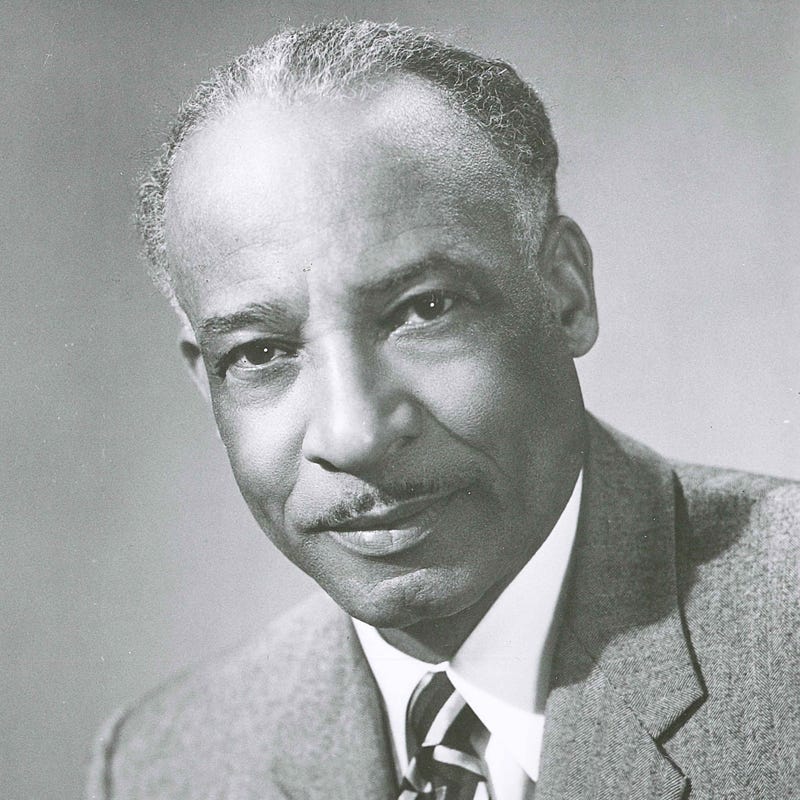

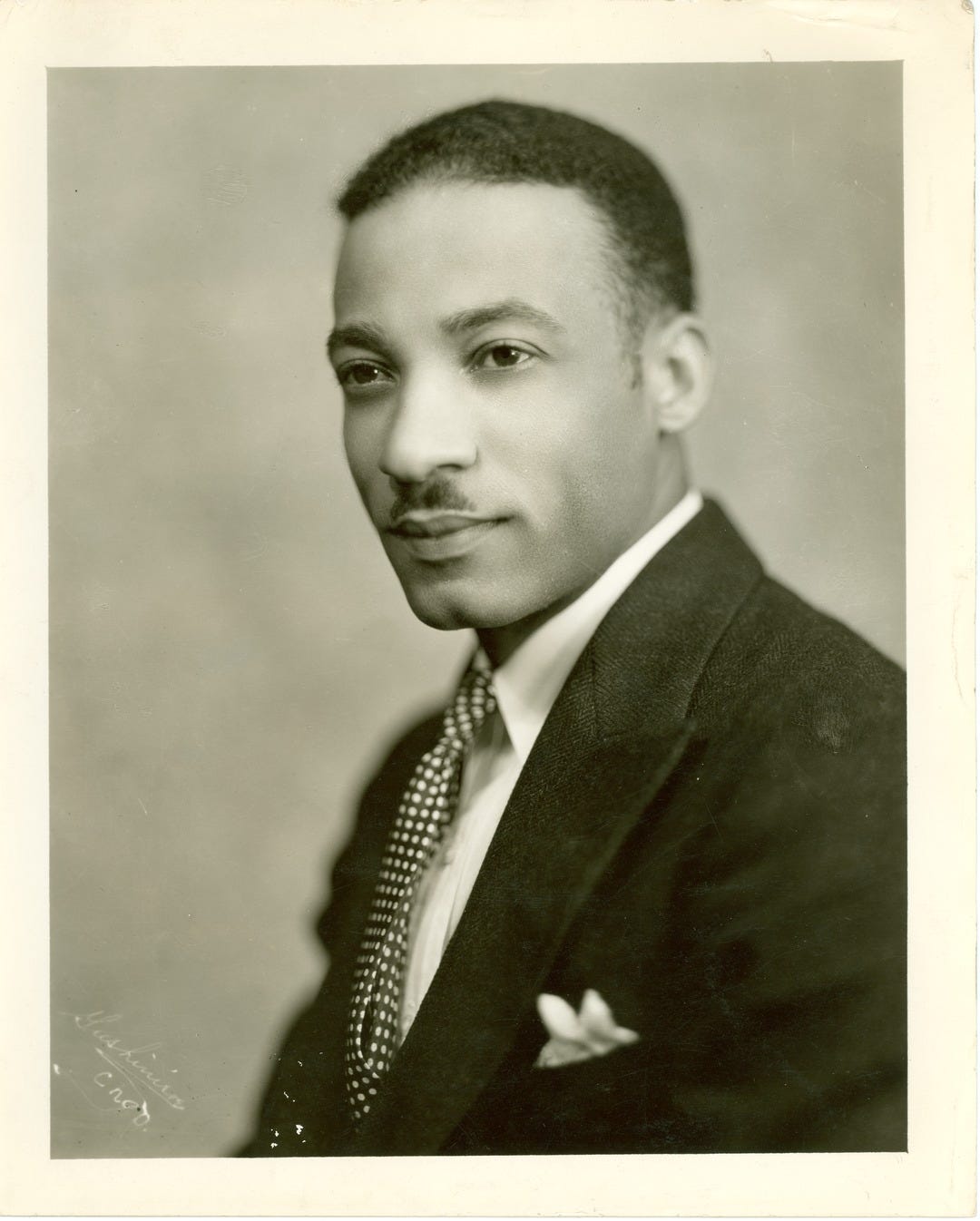

The African American composer William Dawson was born in Anniston, Alabama, September 26, 1899. He moved to Chicago to attend the Chicago Musical College and the American Conservatory of Music, playing trombone in the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, 1927–30. He taught music conducted the choir at Tuskegee Institute 1931–56, greatly influencing generations of students and faculty.

He began to compose at a young age, writing chamber music including a piano trio and a scherzo for orchestra, but he is best known today for his arrangements of spirituals. This recording of Dawson conducting his arrangements with the Tuskegee Institute Choir is extraordinary.

However brilliant his spiritual arrangements are, it is imperative we bring his Negro Folk Symphony back into the repertoire. While on tour with Tuskegee Institute Choir, Dawson showed this extraordinary score to Leopold Skokowski, who immediately fell in love with it. In 1934 Leopold Stokowski and the Philadellphia Orchestra premiered the work to great acclaim, with the glorious end of the second movement receiving spontaneous applause. Dawson wrote that that entire symphony is unified by a music call, “symbolic of the link uniting Africa and her rich heritage with her descendants in America.”

It was the great Czech composer, Antonín Dvořák, who showed us how to use our folk music by writing his Symphony №9 “From the New World” by using spirituals and Indian dance rhythms, as he did with Bohemian folk songs for his earlier symphonies, in order to create an uniquely American music. In his symphony, Dawson quoted the spirituals,“Oh, My Little Soul Gwine Shine Like a Star” and “Hallelujah, Lord, I Been Down Into the Sea.” Dawson agreed with Dvorak, writing, “but these are folk songs and we have got to know and treat them as folk songs because they contain the best that’s in us. And anywhere in the civilized world, when you say, ‘This is a folk song,’ all the nations prize their folk songs. All the great composers utilize their folk songs, their source of material for development.”

In 1952, after a trip to West Africa, Dawson revised his symphony by incorporating more percussion instruments and tightening its structure. In 1963, Leopold Stokowski would return to the piece he premiered nearly thirty years prior to record this revised version with the American Symphony Orchestra. It has luckily been remastered for all to hear.