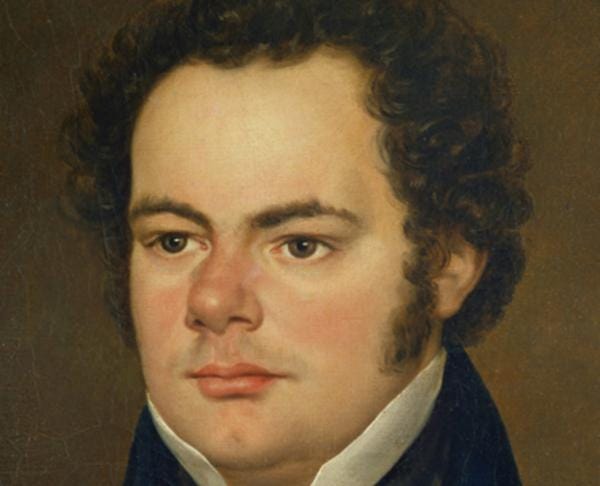

Franz Schubert (1797–1828) wrote a series of eight solo pieces in 1827, two of which were published in his lifetime, with all eight eventually being published as two sets of four impromptus after Schubert’s death. I find it interesting that it was Schubert’s publisher that gave the name impromptu to all eight pieces, not him.

Before I continue, don’t get confused by the two different cataloguing numbers that you’ll see with Schubert’s works. They were first published with “opus numbers,” in the 19th century and then re-catalogued in the mid-twentieth century by the musicologist, Otto Erich Deutsch. So, the first set is Opus 90 and D(eutsch) 899, and the second set is Opus 142 and D(eutsch) 935.

The name, “impromptu,” is as it suggests. These pieces are free-formed works that have no relationship to each other and don’t necessarily follow a strict compositional structure. They are like four miniature drawings that were drawn at the same time but have completely different subject matter, or four small vignettes of completely different characters performed by the same actor.

Schubert was greatly impressed by the impromptus of the Bohemian composer and pianist, Jan Václav Hugo Voříšek, who wrote a series of them beginning in 1817. In fact, it looks like Voříšek, or his publisher, may have coined the term. Here’s an excellent recording of these lovely pieces performed by Artur Pizarro.

Schubert’s Impromptus have been used in popular culture, including the French films, Trop Belle de Jour, L’Homme du Train, and Amour. Impromptu №1, D. 899 was also used as the basis for the score for Alec Guinness’ Smiley’s People.

The pieces take on completely different characteristics when you hear them played on modern piano vs. a piano from Vienna of the early 19th century. One is built for a concert hall and the other for a drawing room. Lambert Orkis’ recordings of the impromptus was, in fact, one of the first recordings I had heard with a fortepiano when it was released in 1990. Listen to the difference in colors between loud and soft on this remarkable instrument.

This is also another excellent recording of the impromptus on a pianoforte performed by the great artist, András Schiff.

In these performances on this type of instrument you hear music that is intimate and quiet. It’s almost hard to believe that they could ever be performed in a concert hall!

However, the pieces endure regardless of the instrument because they touch the soul in such a direct way. Very few pieces have ever touched me like these pieces and I feel lucky to know them.

Edwin Fischer has sublime recordings of the Schubert impromptus and I might listen to these recordings more than any other.

More historical recording enthusiasts would argue that Artur Schnabel’s recordings are non pareil. I’m not going to disagree, I have them in my collection as well. I just think Fischer’s recordings are just as good.

András Schiff has also recorded them on a modern piano and I love them, as I love all of Schiff’s recordings, for their directness.

However, I think the greatest modern recordings were made by the extraordinary Polish pianist, Krystian Zimerman.