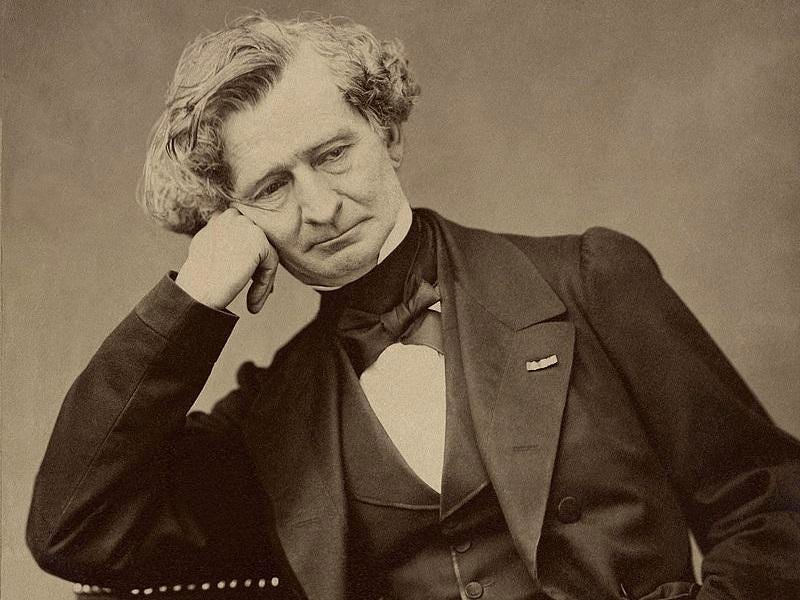

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) was a French composer whose works can truly be called revolutionary. There are many reasons why his works often don’t follow any regimented form and this isn’t the place to go into detail, but his most famous work, the incredibly unique and visionary, Symphonie fantastique, is a perfect example.

What makes this symphony stand out? For starters, the art of writing a symphony was predominantly a German composer’s undertaking. Ballet and Opera were what the French excelled at composing and French Grand Opera was what ruled Paris for most the 18th and 19th centuries. However, I should take this opportunity to introduce to you one of my favorite composers that has been unjustly obscured by history, Étienne Méhul, whose symphonies were profoundly influential on Beethoven’s symphonic writing. Check out Méhul’s Symphony №1 from 1808/09 and you can hear where Beethoven got a lot of his ideas, particularly for the more tumultuous moments of the symphonic form.

Berlioz wrote Symphonie fantastique in 1830 when he was 27. I should note that this is just six years after the premiere of Beethoven’s Symphony №9. I mention this because these two symphonies couldn’t be more different from each other and it always shocks me that these two symphonies are basically contemporaneous.

In 1822, Berlioz fell in love with the Irish actress, Harriet Smithson. It took him seven years to convince her and in 1829, she finally relented and they married. He decided to memorialize his obsession and courtship with this symphony a year into their marriage. He decided to give his beloved a musical theme — an idée fixe — that would appear in each of the five movements. Now, the idea of a musical idea being used in every movement of a symphony wasn’t a new one. In fact, Beethoven did this in what is the most famous symphony ever written, his Symphony №5. However, while ba ba ba baaa is used in every movement — it’s just four notes — it’s not really a theme, but more of an idea. In music, this is called a motive. Berlioz decided to use a lovely theme that is obvious in every movement, and this had never really been done before.

Here is a great Keeping Score documentary and concert by the San Francisco Symphony and Michael Tilson Thomas of the Symphonie fantastique.

I have been a fan of this symphony since hearing the first recording of the Philadelphia Orchestra with their then new music director, Ricardo Muti. I think it’s still a great performance, full of passion and drama.

One of the great interpreters of Berlioz was the Alsatian conductor, Charles Munch. His recording with the Boston Symphony Orchestra from the early sixties is full beautiful colors and imagination.

And this incredible film with the same forces from about the same time is indispensable.

Another classic recording with one of the greatest conductors ever is with Sir Thomas Beecham and Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Francaise. Just listen to the lush sound he gets from the strings.

I absolutely adore the conductor, Mariss Jansons. Sadly, he recently left us and I will probably do a blog solely on him soon. This piece was one of his specialties and he left us with many great recordings and video performances that we can hear and see. However, I think that this performance from 2001 with the Berlin Philharmonic might be my favorite.

A close second would be this video with Jansons and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in 2013.

Another great Berlioz interpreter who truly embodies the ethos of the French sound is the great Swiss conductor, Charles Dutoit. This video is a wonderful example of his artistry.

And the great English conductor, Sir Colin Davis, simply can never go unmentioned when Berlioz is the subject. He had a great love of the composer throughout his entire career and his recordings stand out as some of the very best. His final recording with the LSO is a great way to end this exploration.